A beginner's guide to how modern economies work

A nation’s currency is a public tool that should be used to serve the people.

The concepts below are not limited to large countries like the U.S. We need a fresh perspective for how powerful a public currency can be to improve living standards and to develop and employ any nation’s resources in the service of local communities, national needs, and more. We hope this site can serve as a starting point for many around the world to begin to rethink how the economy and the currency work best together, and to influence public policy in beneficial ways. Read, question, ponder, and share—as people like you learn and get involved, there is no end to the positive changes that can result!

Most national governments issue their own currency. Why does this matter?

Most national governments issue their own currency. Why does this matter?

Most national governments actually create their own currency. This means they can, and should, behave very differently than all the businesses, households, and local governments that use that currency.

When nations constitute a government, they grant that government the power to issue a public currency. Governments need resources and workers in order to serve the public. The currency is the tool governments use to obtain such resources. Today, this is mostly done with computers and bank accounts – governments make all their payments simply by creating deposits in bank accounts.

A tool To serve the Public

The reason we have a currency is the same reason we have a government – to create, protect, and develop a society within a given sphere of influence. Countries desire to develop and improve their quality of life and the currency is their primary tool to do so.

A government with monetary agency is able to pay for those things that serve the needs of society as a whole and that we desire to be provided to all, not just those who can afford them. The government can make investments in things like defense, research, health and education that serve even remote communities and are not profit-making.

In addition, when the government invests in these things the private sector does not have to go into debt in order to fund them. This allows private sector debt to be reserved for those things that are profitable or not for collective benefit, while the government makes those investments that serve society as a whole.

Countries can use their national currency to best utilize their available resources, develop domestic productive capacity, and raise living standards in ways that benefit all.

How are national currencies created?

How are national currencies created?

A nation’s currency is typically established under a constitution or law, granting the government unique powers to issue the nation’s currency. The general rule throughout history has been “one nation; one currency” and there’s a good reason for this as we’ll soon see.

We can simplify the mechanism of creating a currency down to three main steps:

- Government chooses a unique national monetary unit (e.g. Japan chose the “Yen”; the U.S. chose the “Dollar”).

- Government issues currency denominated in that unit to pay for public resources and labor.

- Government impose taxes, fines, tariffs, or fees that can only be paid with the government’s currency to create demand for its new money.

Once established, the government’s currency usually becomes the de facto unit for contracts, wages, and commerce.

How do modern governments get money for public needs?

How do modern governments get money for public needs?

Governments make payments by increasing bank account deposits

It may sound odd to hear it said this way at first given all the images of government’s running printing presses, but it’s quite accurate.

Banks have special accounts with the Central Bank (the Federal Reserve in the U.S.) – called reserve accounts. When the government pays a federal judge, buys a military vehicle, or sends a payment on behalf of a hospital patient, the Federal Reserve marks up the balance in the reserve account of the recipient’s bank. Those bank deposits represent newly created government currency. The bank then marks up the deposit balance for the recipient’s bank account for the same amount.

Governments make payments simply by adding numbers to bank accounts with computers.

There is no reason the government needs to “get” numbers before it can “add” numbers. It doesn’t need any stack of gold bars or paper notes it has collected from people before it can type those numbers. In the process of making any payments, the government simply creates bigger bank balances that represent its currency.

This is, of course, a big responsibility and we certainly need transparent and accountable public processes to ensure our government uses its currency-issuing powers to serve the public.

Can the government run out of money?

Can the government run out of money?

Currency-issuing governments can always pay their bills

A nation that issues its own currency can never go bankrupt or be unable to pay its bills, as long as those bills are due in the money they create. That includes promises to bond holders to pay interest, promises to retirees to pay them a decent income in retirement, or promises to veterans or the general public to pay for their medical care.

If any financial obligation is due in U.S. dollars, then the U.S. government always has the financial means to pay it. An authorization from Congress is all it takes for the Treasury and Federal Reserve to make the necessary deposits.

Now if a country is short of things it needs like medical supplies or food, it may not be able to use its own currency to pay for those necessities since they are not available for sale in that nation’s currency. There are definitely real limits to consider, but running out of its own currency it not one of them.

Do currency-issuing governments have limits to what they can buy?

Do currency-issuing governments have limits to what they can buy?

While the ability to create currency is not a constraint, there may be limited availability of real resources

Understanding modern money can help nations better steward and utilize their available resources and labor.

Governments create money every time they spend and have the capacity to do so without limit. Of course, that doesn’t mean that money solves all problems nor that the right answer is always to have the government pay the bill. Having the ability to credit bank accounts doesn’t solve all real-world challenges, and in many cases it may be better for non-government entities to provide the funding.

However, if known needs can be met with resources available for sale in a nation’s currency, we can remove the excuse that the solution is unaffordable, and instead focus on if we want to use our available resources to meet this need, and if so, what approach is best. In such cases, public funding is always an available option.

The currency is a tool, and it can be used to mobilize the economy to wage war just the same as it can be used to mobilize the economy to provide health services or to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It is also important to recognize that having the government pay for something that requires public funding does not necessarily have to mean that the government should manage that activity. There is plenty of room to debate what we want our government doing and paying for, but we should first make sure we have all the right options on the table.

E.g. If there are no health clinics or doctors around to care for the needs of sick people, the ability to pay for their medical bills won’t help them get better. However, if the only thing standing between adding those doctors and facilities is a source of funds, we now know we have a tool designed exactly for this purpose – our public currency.

There is still plenty of room for public debate about the best way to utilize resources and to balance public and private interests.

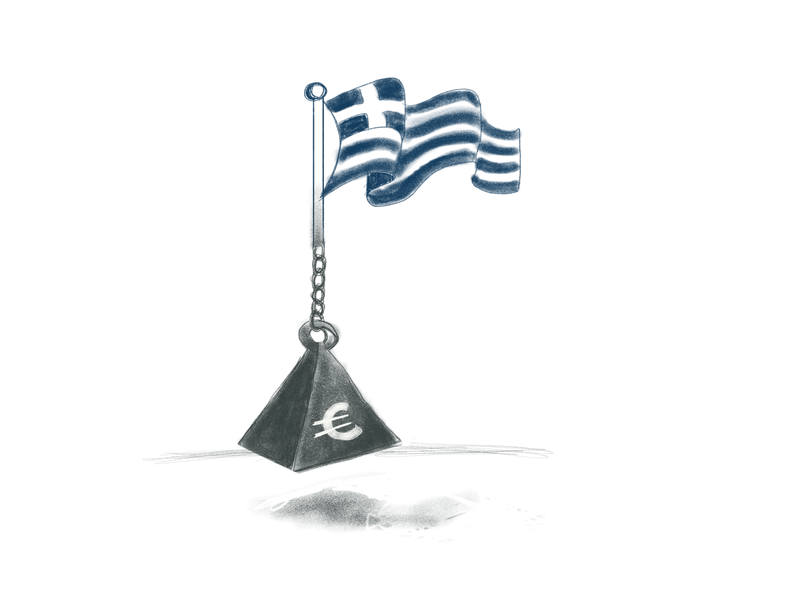

What about Greece and other nations which get into financial trouble?

What about Greece and other nations which get into financial trouble?

Not all nations have the same level of monetary agency, and this can make a big difference

Simple comparisons between the fiscal state of countries like the U.S. and Greece or Argentina are unhelpful because many countries have reduced their fiscal capacity in one or more of the following ways:

- Abandoned a national currency: Greece and all countries in the Eurozone gave up their own national currencies and are now users of the Euro – a currency they do not control and cannot create on demand without tight external controls. In a sense, they are a bit like U.S. states rather than nation-states. Greece must borrow Euros or obtain them via trade. The U.S. creates U.S. dollars any time the U.S. Congress authorizes payments. Big difference!

- Foreign debt: Countries like Argentina that have amassed large debts in U.S. dollars owe their debts in a currency they do not and cannot create. They can definitely get into financial difficulty since they have to earn U.S. dollars via trade or attracting foreign investment to make their debt and interest payments.

- Fixed exchange: Governments which promise to exchange their currency for another currency (or to a commodity like gold) at a fixed rate can face similar problems. They must maintain large reserves of foreign currencies like the U.S. dollar to be able to keep their conversion promise, and many have been forced to default over time.

Some countries are able to get by for some time with these limitations, especially those that have large exports, but this seldom lasts forever. Limiting a nation’s fiscal capacity is a serious matter.

If government payments create bank deposits, what about taxes?

If government payments create bank deposits, what about taxes?

Governments tax by debiting bank accounts

Federal taxation works to reverse what the government did when it made payments. When you write a check to the Treasury for taxes owed, the Federal Reserve, acting in its capacity as the Treasury’s bank, will debit your bank’s reserve account for the amount of taxes. Your bank will, of course, debit your bank account.

The net effect of paying your taxes then is the removal of previously created government currency, in the form of a reduction in your bank’s reserve balance. Banks act as agents in the addition & removal of the government’s currency into and back out of the economy.

- Government payments create bank balances; taxes reduce bank balances.

- Government payments provide income to recipients; taxes reduce spending power.

- Government payments are what creates our base money supply; taxation reduces our money supply for reasons explained in the following sections.

Doesn't the federal government need to collect taxes before it can invest for public purpose?

Doesn't the federal government need to collect taxes before it can invest for public purpose?

It’s actually the other way around: the currency we need to pay our taxes must first be spent into the economy by government – there’s no other way for us to get the currency we need to pay the tax

Notice the logic. Federal taxes return to the government the currency it first created. Only the government can create its currency – we’d be thrown in jail if we tried!

We simply cannot pay our federal taxes until we have obtained the government’s currency. Since the U.S. government will only accept U.S. dollars in payment of taxes, logically, government spending has to happen first. This is, in fact, what happens in modern monetary systems.

The government never needs our taxes before being able to make payments.

Of course, all state and local governments, being currency users like you and I, do still need to collect taxes or borrow in order to spend. They could also receive funds from various agencies of the federal government. The federal government is unique as the issuer of the nation’s currency.

If the government can just create money out of thin air, why does it need to tax us?

If the government can just create money out of thin air, why does it need to tax us?

Taxes ensure there is continual demand for the government’s currency, so that the government can always find willing sellers when it pays

Imagine a government that wants to create a brand new currency; let’s call them GreenBucks (or GBs for short). The government recruits you to work as a teacher, earning 80,000 GBs a year. Would you accept this brand new currency as wages? Can you buy food or a car with those GBs? Could you use your GB income to get a house mortgage? Probably not until somehow the government can get everyone in the economy to convert over to using it’s new currency!

Now, what happens if the government also imposes a property tax on every household and business that must be paid in GBs, and they also established a Central Bank that would facilitate GB payments between all the nation’s banks. Now, almost everyone in the nation owes GBs to the government and will accept them in payments. Your local bank will now happily write you a mortgage in GBs with that good government job since they now act as agents of the government’s currency and they know everyone will use it for deposits, contracts and loans.

TAXES “DRIVE” THE CURRENCY

Step two in the section How are national currencies created? is critical. By imposing a tax that must be paid using the government’s currency, businesses and households all need to obtain that currency in order to pay the taxes they now owe. This is a simple yet proven and reliable method for any government to establish a currency and ensure it has broad acceptance to enable the government to provision itself.

Countries can, and do, literally create new currencies overnight which are nationally accepted simply by requiring that all tax liabilities must now be paid with that currency.

In this sense we say that federal taxes “drive” demand for the currency. In large economies we lose sight of this underlying feature, and there are certainly other reasons that currencies of many countries can become widely adopted, but in the long run, it is likely that taxation must be collected at some level in order to maintain a stable currency.

Countries that struggle to impose or collect taxes will have a reduced capacity to issue currency to obtain resources and labor and to invest in the development of their nation, but countries that maintain a stable, accountable government with the ability to collect taxes will always be able to find people willing to work and businesses willing to sell goods and services in exchange for their currency.

What other purposes do federal taxes serve?

What other purposes do federal taxes serve?

Taxes create and maintain continual demand for the government’s currency, but they can also be used to further public purpose in several ways.

TAXES HELP MANAGE THE HEALTH OF THE ECONOMY.

Taxes function to reduce spending power in the economy. By reducing spendable income, taxes take away purchasing and borrowing power which in turn can reduce sales and leave people unemployed. By freeing up workers and business capacity to supply what the government needs, taxes can be said to create “fiscal space” for the government to then buy the resources it needs using its currency.

If we look at it from the perspective that the government first spends its currency into the economy then taxes some of it back, we can say that taxes allow the government to obtain necessary resources without straining the capacity of the economy or out-bidding other market participants and driving up prices excessively. In other words, one effect of taxes is to lower the spending of the private sector to offset the government’s spending – i.e. maintaining price stability with full employment.

As we’ll see, it is very important that the government gets the right balance, especially when it comes to causing unemployment. It clearly makes no sense for the government to leave some of the population without the ability to obtain its currency while still demanding more of its currency back from the population in taxes. Nor does it make sense for the government to drive up prices unnecessarily!

TAXES can help reduce inequality

Excessive concentrations of wealth and power is a continual threat that democratic nations must guard against. If left unchecked, the country’s resources, democratic processes and institutions can become controlled by, and for the benefit of, the wealthy to the detriment of the general public. Taxation is one tool governments have to help push back against this tendency and to maintain a more equitable society.

What the government taxes, and how much the government taxes, makes a big difference in the “shape” of our economy. Extreme lopsided wealth is a result of policies designed to create it, and different policies could create a more balanced economy. For example, by lowering taxes on capital gains while raising it on wages, we make it easier for capital to accumulate in the hands of the wealthy while also making it harder for most workers to build wealth. Tax policy matters.

Taxes serve public purpose

Taxes influence household and corporate behavior, and are therefore effective as incentives and disincentives that can help direct private enterprise and consumer behavior in the public interest.

For example, a nation that implements a carbon tax is not fundraising for the government coffers, but seeking a method for shifting the economy toward a more sustainable energy solution. Therefore, the ideal carbon tax would collect zero taxes since it would have ended carbon-based energy generation!

Therefore, we should always think of tax policy as its own domain, separate from decisions related to government investments in public priorities. Options for who to tax, how to tax, and how much to tax should all be analyzed carefully for their effects on the economy and implemented to best serve public priorities and goals. But taxes should never be assessed based upon the false notion that taxes “raise funds” for a currency-issuing government.

Won't too much government spending cause inflation?

Won't too much government spending cause inflation?

INFLATION FEARS ARE OFTEN EXAGGERATED

The causes of inflation are poorly understood and even agreeing on a consistent definition can be difficult. Inflation is neither good nor bad in itself; rather we should be assessing inflationary effects (which are often industry-specific and localized) in relation to the quality of life and living standards of our nation’s local communities. Inflation can bring benefits and harms, and sometime both to different groups. Where inflation problems do arise, the cause and solutions may be more related to other local or federal government policies than the amount of government spending.

Inflation is not, as is often feared, an automatic result of government deficit spending, and is very often localized to specific areas of the economy. It is best to look first at the causes of inflation before making general comments about the influence of government spending.

The common belief that inflation is the result of government spending is incorrect for several reasons, including:

- Countries that import more than they export usually require continual government deficits to keep the domestic economy growing;

- Money saved is not money spent and therefore can’t be inflationary – economies with high rates of savings (such as retirement accounts) from aggregate incomes may require continual deficits to maintain economic growth;

- The government can choose what prices it pays for labor and resources so it doesn’t have to drive up market prices as it increases its role in a sector of the economy to serve a public need;

- Some government policies might be deflationary if they are more efficient that the existing system. For example, a universal health system paid for by the federal government could possibly reduce costs and administrative inefficiencies compared to the current private system in the U.S.

- The private sector could be the main cause of an inflationary problem, driven by a monopolistic market or an excessive expansion of bank credit (e.g. the 2000 Dotcom & 2008 Housing Bubbles in the U.S.) — even as government spending could be decreasing.

- The private sector may have capacity to expand production to meet increased demand without price increases.

- The government and/or the private sector may use a rise in price levels to innovate and solve the problem giving rise to rising costs (natural gas fracking and renewable energy development in response to high oil and gas prices is a good example).

GOVERNMENTS CAN CERTAINLY CREATE CONDITIONS THAT DRIVE UP PRICES, BUT THEY CAN ALSO (& FAR TOO OFTEN) CREATE CONDITIONS THAT STARVE THE ECONOMY & CREATE UNEMPLOYMENT

The government plays a powerful role in determining the structure of markets and prices. It is the sole issuer of the currency, the primary legislative agent, and the regulator of the financial sector. Warren Mosler states that “inflation is a function of the prices paid by the government”. What the government pays for, how much it pays, how it sets and enforces its laws, how it regulates banks and credit — all these functions serve to shape the stability of prices in the economy in a material way.

For example, the wages that the government pays its workers and the rules it sets for minimum wage labor will have a significant effect on the price level — positively or negatively. Governments can set conditions that provide a decent base living wage or conditions that allow for poverty-level work conditions. Unfortunately, many countries set this bar too low leading to unnecessary levels of austerity and its accompanying social problems.

Governments can also out-bid any private sector business or even control sectors of the economy, such as education, public infrastructure or health care (nations choose varying approaches). If governments compete for scare resources or drive up wages of high-demand skills, that may create inflationary conditions in some sectors of the economy.

So governments should be held accountable to act responsibly:

- to not escalate payments for resources and labor in ways that lead to inflation levels that become harmful to public purpose;

- to maintain careful oversight of the financial sector and other industries to prevent speculative or fraudulent credit expansion and monopolistic or anti-trust pricing power;

- and to maintain full employment and acceptable base living conditions to prevent deflationary conditions and unnecessary austerity among the population.

Unemployment is a serious social and economic problem, and governments have been guilty far too often of not managing the currency in a way that maintains domestic full employment and acceptable base living standards.

While inflation can certainly be a legitimate risk, it can also be said that we too often allow the fear of inflation to be used as an excuse to avoid addressing the significant problems associated with persistent unemployment, and a lack of continual maintenance and development of public infrastructure.

The size of a country’s government is a political choice – we can all debate what we want our government to fund and whether to have a bigger or a smaller government. But for whatever size of government we collectively choose through our political process, the right amount of taxation is that which leaves the economy at full employment without persistent and excessive inflation.

A FOCUS ON LIVING STANDARDS IS KEY

Finally, there is actually little evidence that moderate rates of inflation have an overall negative effect on society, as long as living standards and the quality of goods are improving. However, the ill effects of persistent unemployment and underdevelopment are real and deserve far more attention than they are currently given in how the government evaluates its approach to taxation and investment.

Surely the government can't just create currency without constraint?

Surely the government can't just create currency without constraint?

THERE ARE CONSTRAINTS, BUT GOVERNMENTS CAN PAY FOR ANY REAL RESOURCES THAT ARE FOR SALE WITH THEIR CURRENCY

A nation that has no oil cannot issue its currency and make oil appear. The government’s currency isn’t a magic wand to fix real world constraints, but it is a tool to help deploy available resources that would otherwise not be utilized, our could be put to better use, to meet needs.

Each time we ask the question “can we afford to…[name your preferred public policy]?”, the first step should always be to evaluate the real resources needed; to determine if we have the people, knowledge, and resources to meet the need. If the resources are available or can be made available, the ability to credit bank accounts simply takes a vote by Congress to authorize the investment to serve the public need.

Anything we don’t have domestically, we have to find a willing supplier who will trade in our currency. If not, we may have to export enough to obtain the foreign currency we need to procure these resources.

WHAT WE CAN AFFORD IS ALWAYS MEASURED IN REAL RESOURCES, NOT MONEY

If we ask, “Can we build a national high speed rail system?”, the answer isn’t whether we have enough money but whether we have enough engineers, construction workers, raw materials, and knowledge of the technology to design and build such a system. Do we have the political will and public support to do so? Are we willing to use the necessary real estate for this purpose? If the answer is yes, then Congress can approve the funding. Congress never needs to “find money” since they control the currency.

Countries that lack all these resources will have to import everything but perhaps labor to build a high-speed rail system. Some may have sufficient trade relationships such that they can import the trains and consultants. Others may need to use their export capacity for more pressing needs, in which case they cannot afford the rail system yet.

REAL RESOURCES ARE CONSTRAINTS; CURRENCY IS NOT

The availability of the real resources that can be obtained with the national currency is where our limits lie. Sometimes we can develop more capacity through prudent investment. Sometimes we have no means and must choose between alternatives or obtain from abroad via trade. Governments can’t use their currency to buy what is not for sale in their currency, but where a nation has idle resources for sale or people willing to work for its currency, it can always afford them.

We suggest that nations should always be seeking to develop their capacity to improve living standards especially for their most dependent citizens, and should use their currency to full effect to do so.

Don't we need budget rules to keep the government accountable?

Don't we need budget rules to keep the government accountable?

WE NEED ACCOUNTABLE GOVERNMENT, BUT HOUSEHOLD BUDGET RULES ARE INAPPLICABLE AND HARMFUL WHEN APPLIED TO THE CURRENCY ISSUER

We all want a government that serves the public well and behaves in a responsible manner. The question is not whether we want government to be accountable with its currency-issuing power, but rather what is the right way to hold it accountable.

DEBT CEILINGS CREATE POLITICAL GAMESMANSHIP WITH THE ECONOMY

A “debt ceiling” rule makes no sense (few countries even try this) since it tries to impose a limit after-the-fact on decisions the government already made with respect to public investments and tax policies. The size of a government deficit is the result of factors out of its control, such as a sudden market collapse and recession or an expansion in business. The deficit itself is not what we should focus on when designing public budgets, but rather what we want/need our government to pay for, and how to do so in a way that leaves the economy in a healthy balance. A debt ceiling is largely used as a political ploy and serves no useful purpose in a functioning democracy.

BALANCED BUDGETS ARE DISASTROUS WHEN APPLIED TO NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS

“Balanced budget” rules are even worse than debt ceiling rules because they seek to impose strict guidelines that may apply to currency users (households, businesses, local governments) but are inapplicable and harmful when applied to the public currency. Such rules ignore the fact that the government has a unique responsibility to meet the demand for its currency, in much the same way that a water utility has a public duty to serve the needs of all households and businesses, not to artificially constrain supply based on arbitrary rules that could leave citizens without essential water supply. Controlling the addition of currency based solely on tax receipt forecasts is extremely harmful to the economy, businesses, and the people the government is serving. Trying to enforce such policies will create unnecessary austerity, underinvestment and unemployment.

PUBLIC DEBATE AND OPEN DEMOCRATIC PROCESSES ARE EFFECTIVE TOOLS TO KEEP GOVERNMENT’S ACCOUNTABLE

The public want their government to use its power for public good without corruption or waste. We need open and accountable public debate on what we want our government to invest in and how it should tax. Fair elections, equal representation, and robust, transparent public debate is still the best way for the voting population to influence and change those in political leadership who are not serving the public well.

It is critical that the public understand the public currency so that it doesn’t get trapped into supporting policies that undermine their interests. Supporting inapplicable household budget balancing practices is one example of a badly misled public.

It is very common for nations to need continual government deficits — i.e. government payments exceed what is removed in tax receipts, leaving the difference in the economy — in order to offset trade balances, meet demand for domestic savings, and generally to maintain a fully-employed private sector and a growing economy.

As we evaluate both public investments and tax policy, we should take care to always evaluate each on their own merits and avoid the trap of creating a “pay for” link between tax policy and public needs.

Doesn't the government have to borrow when it spends more than it taxes?

Doesn't the government have to borrow when it spends more than it taxes?

Governments can’t borrow what they can create on demand

Since currency-issuing governments make all their payments simply by crediting bank accounts using computer entries, they do not need to – and in fact can’t – “borrow” the currency they create on demand. Unfortunately, we’ve done ourselves a big disservice to use the word “debt” when we reference outstanding government bonds. It’s an unfortunate vestige from our gold standard days.

What we call government “debt” – e.g. Treasury bonds in the U.S. – can only be purchased with government currency (e.g. Central Bank reserves or settlement balances). In order to buy a bond, the purchaser must already have sufficient currency in a bank account to buy the bond. In other words, bonds are all purchased with bank account balances that were increased as a result of prior government payments.

Bonds cannot be a source of Currency for the government

Just as taxes cannot be paid until we first obtain the government’s currency, so also bonds cannot be purchased until the government makes enough of its currency available to bond buyers. Government payments for goods or services increase bank balances which can then be used to buy bonds, not the other way around. We need the government to spend its currency into the economy before we can buy the government’s bonds!

This fact was well known a few decades ago during World War II as the government in the U.S. ramped up the war effort, injecting large increases of currency into the economy. War bonds were part of a successful marketing effort by the government, in lieu of raising taxes higher, to get consumers to not spend all their income to help prevent inflation (bonds themselves don’t prevent inflation – the reduced consumer spending was the key). War bonds did not “give the government dollars to spend”.

Think about it for a moment: if the “national debt” grew from $1 trillion to $2 trillion, where did the population get the extra $1 trillion in currency to buy the bonds? It must be the result of increased government payments, net of taxes. Hence, we can say that bond sales are ex post: i.e. they occur after (sometimes on the same day) the government makes new payments.

Could governments just stop issuing bonds?

Governments do not need to issue bonds in order to make payments. Whether $1,000 of currency remains as a bank deposit (i.e. a “reserve account balance” at the Central Bank) or is saved in the form of a $1,000 Treasury Bond (i.e. a “securities account balance” at the Central Bank) has no bearing on whether a nation’s government can authorize another payment to be made. These are basically two different types of Central Bank accounts representing dollars that the government has spent into the economy. The government’s ability to make payments is unaffected by whether numbers are in one account or the other.

Perhaps we should just direct our governments to stop issuing bonds altogether so the term “debt” is no longer associated with our base money supply. This might help us leave behind the harmful fearmongering about government deficits and refocus on how to best use our public currency to serve the public.

So what is the National Debt?

So what is the National Debt?

THE TOTAL AMOUNT OF payments the government has made into THE ECONOMY less the total amount removed via taxes forms our base money supply — which normally grows with the economy

Each year that the government adds more to bank accounts than it subtracts, the balance remains in bank accounts somewhere in the economy. We call this difference a deficit because we label it from the government’s perspective. It is equally true that this same sum is a “surplus” from the perspective of the rest of the economy. Balance sheets must balance. When the government leaves currency in the economy, that means it is being saved somewhere in the economy.

For example, if in a year the Australian government invested $500B into the economy and taxed $400B, there is now an additional 100 billion Australian dollars being saved somewhere in the world (some domestic, and some with trade partners, investors or currency traders).

In other words, these accumulations of currency in the economy are exactly equal to the collective savings of the government’s currency. Every year as the government leaves more currency in the economy than it removes, the base money supply increases. This is quite normal for growing economies.

What we misleadingly call the “national debt” is just the portion of that base money supply that has been transferred into interest-bearing accounts at the Central Bank called bonds.

Do Governments Still need to Sell Bonds?

Back when some nations promised to convert their currency to gold under a fixed exchange rate system, bond sales were a way for governments to protect their gold reserves. If you purchased a $1,000 Ten-Year Treasury Bond, $1,000 of government currency could not be converted to gold for ten years. Under this arrangement interest rates were determined by the market as the government had to give an incentive to savers not go after its stock of gold each time bonds matured. All this changed once nations stopped promising to convert their currency to gold – a promise none of them could keep anyway during times of war or crisis.

There is no longer any need for national governments to sell bonds denominated in their own currency. Countries that offer bonds of varying terms that earn interest do so by policy choice, not necessity — except for countries like Greece that no longer issue a domestic currency or have otherwise restricted their fiscal capacity. Governments that continue to offer bonds are simply giving away more public dollars (or Yen etc.) to people who already have dollars. The interest rate given is a policy choice usually determined by the central bank, not by private markets.

SO WHAT ARE GOVERNMENT BONDS Today?

The government offers special savings accounts for those who save its currency. In the U.S., these government securities – tradeable interest-earning accounts – are called Treasury Bonds (for longer terms) and Treasury Bills (for shorter terms).

Unlike the debt of households and businesses, where repayment depends on revenues, the government needs no revenues to “repay” these savings accounts. When they mature, the Central Bank simply transfers the balance from the securities account back to the reserve account of the bank receiving the funds.

BUYING BONDS IS LIKE MOVING FUNDS FROM A CHECKING ACCOUNT TO A CERTIFICATE OF DEPOSIT

Imagine you had $10,000 in a checking account and you put it into a Certificate of Deposit (CD) at your bank for one year. When the year was over, the bank transfers the funds back to your checking account. That’s basically all that the Central Bank is doing when someone buys a government bond and holds it to maturity. The government is no more in debt when it sells a bond than your bank is more in debt when you transfer dollars from a checking account to a CD.

We should stop referring to our base money supply by the outdated and misleading term, “national debt”. There is no risk of insolvency or bankruptcy for monetarily sovereign governments.

What does it mean for the government to balance the economy, not a budget?

What does it mean for the government to balance the economy, not a budget?

GOVERNMENT PAYMENTS PROVIDE INCOME, PROFITS & SAVINGS TO THE PRIVATE SECTOR — THEY SHOULD ALWAYS BE AT A LEVEL SUFFICIENT TO MAINTAIN FULL EMPLOYMENT

Modern economies run on sales. Without enough sales, the economy falters. Businesses need to sell what they produce or they won’t invest in growth and may cut back on employment. When the businesses of a country pay workers and the workers all save some portion of their money or buy foreign-made goods, that income isn’t buying the output those workers produced. Unless those lost sales are replaced, the economy will contract as businesses reduce their production.

There are four main ways a domestic economy can sell more of the output it produces:

- Foreign trade (import less; export more)

- Domestic debt (consumers or businesses borrow to spend)

- Reduce savings (consumers or businesses spending from savings)

- Government deficits (reduced taxes and/or increased investments)

As the currency issuer, #4 is the only factor we can always count on to help, since we can’t control other nations’ trade policies and the private sector can only take on so much debt before it becomes unable to keep up with the payments.

THE IMPORTANCE OF “SECTORAL BALANCES” & GOVERNMENT FISCAL POLICY

When we talk about “the economy” we are usually talking about all of a nation’s domestic businesses, households, local governments and other institutions.

It can help to think about a nation’s currency in three general categories:

- the foreign sector (all the countries that they trade with),

- the private sector (really the whole domestic economy excluding the national government), and

- the government sector (the issuer of the currency that adds and removes dollars as it invests into the economy and taxes back out.)

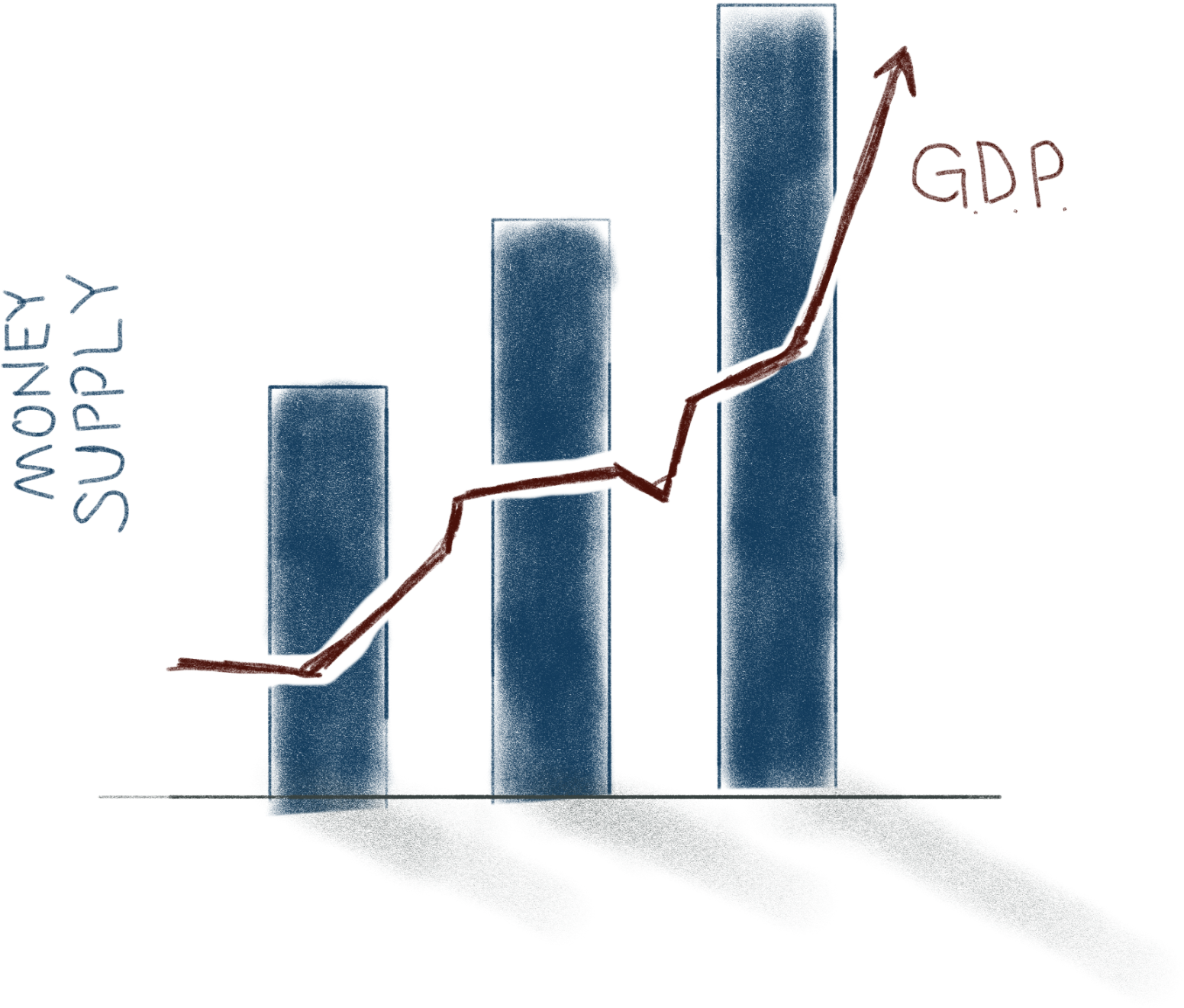

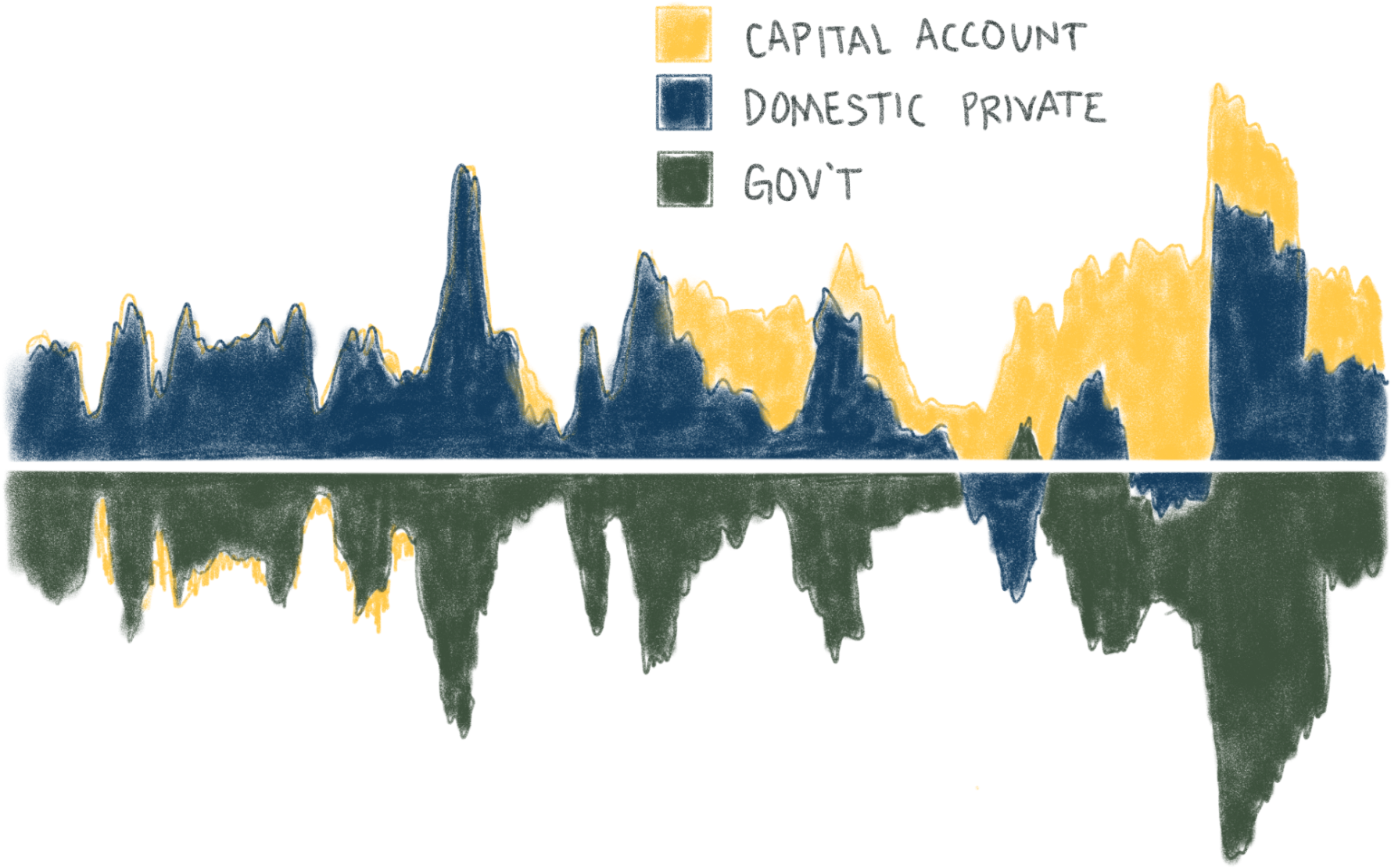

The chart image below is based on data from the U.S. economy but the same chart can be made for any country & currency. These three sectors are always in balance in terms of the currency. A surplus of dollars in one sector must mean a deficit of dollars in at least one other sector. Countries like the U.S. with large imports start off with a large deficit to the foreign sector’s surplus (other countries saving our currency via trade).

All else being equal, the private sector would have to constantly increase its indebtedness at least as much as the trade deficit just to stay even. This can obviously become unsustainable — it far is better that the government continues to add more (or remove less) of its currency to compensate for trade deficits and keep the household and businesses from excess debt. It can do so forever without running out of money or becoming insolvent.

Our surpluses (savings) drive demand for Government deficits

In reality, the domestic economy almost always wants to net save money (they don’t want to spend all their income). The currency issuer has a responsibility to ensure that it is adding enough into the economy, net of taxes, to meet the desire for savers. If it doesn’t, it is like a public water utility that fails to supply enough water to meet the demand of businesses who use it in production and households that fill swimming pools. It would be irresponsible to let people go thirsty because they didn’t account for the extra water needs in the city.

Like a public water utility, the government holds a monopoly on the issuance of the sovereign currency. In this role, it bears significant responsibility for any lost output and unemployment that results from poorly managing the net amount of currency it adds or subtracts from the economy. The currency issuer should always manage its flows with an eye on the demand for money and the productive capacity of the whole economy.

Budget balancing is good for households but is the wrong tool for the wrong entity when it comes to the national government.

Why do most nations have their own currency?

Why do most nations have their own currency?

Public CURRENCIES ARE THE PREFERRED WAY FOR GOVERNMENTS TO OBTAIN ALL THE RESOURCES NEEDED TO FULFILL THEIR OBLIGATIONS TO SERVE THE PUBLIC

Whether we choose a larger or a smaller role for our government, all of the public institutions that serve the people need to obtain real resources – labor, materials, goods, & services.

Rather than taking them with brute force, most modern nations prefer that their government purchase the resources they need. That’s a good thing! For this reason, most countries give their government authority to issue a national currency.

When countries share a currency, such as in the Eurozone, there is a higher risk that the currency won’t be used by those in power to serve the needs of all countries and communities alike. Just ask Greece!

Nations have currencies for the same reason they have a government: to serve the public – to do things together that can’t be done alone – to develop the nation.

Of course, we recognize that many communities are still excluded from benefiting from public investment even in nations with strong public currencies, and we encourage creativity and a much broader agency to re-imagine ways to care for our shared world and improve living standards for all.

The currency is a public tool that should serve the needs of the people.

How does an understanding of modern money theory help us think about good public policy?

How does an understanding of modern money theory help us think about good public policy?

Nations that issue their own currency are not constrained in the same way that currency-using governments are constrained. This has a profound impact on the range of policy options available to such governments that are not available to those with less monetary sovereignty.

This doesn’t mean the answer to every problem is the government, nor that everything we choose to do as a nation should be funded by the government. The debate over public policy is important and differences of opinion will remain: however, the debate should not place artificial constraints on the ability of the government to make payments if that is in the public interest. Rather, our focus can be on the effects of each policy on available resources, on impacted sectors of the economy, on local communities, on ecosystems (i.e. on all the things that matter in the real world) and then to determine what is in the best interests of all constituents.

ENDING UNEMPLOYMENT

An important example is unemployment: we now know that governments can afford to employ everyone who is willing to work for the government’s money, and that the effects of doing so can stabilize and grow the economy while making a meaningful impact on the many social problems that arise from unemployment.

REDEFINING FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY

We need a new definition of what it means for the issuer of the currency to be “responsible” fiscally. It cannot mean balancing a budget like a household. Rather, it must have more to do with how well the government fulfils public purpose, ends involuntary unemployment, and fosters the continual increase in living standards and health for all of its population.

HOW SHOULD YOUR COUNTRY USE ITS CURRENCY TO SERVE?

As we fully comprehend the power of a public currency, we can rethink much of our policy debate without the constraints of a scarce money supply. What would you want the currency used for?

- Fully staff public services in every community, including courts, public defenders, law enforcement, teachers, librarians, …?

- Reduce corporate or payroll taxes that don’t serve a public purpose?

- Take bold action to address climate change without harming economic growth?

- Invest in public infrastructure especially in cities and towns that do not have sufficient population to fund it themselves?

- Reduce the burden of health care from businesses by investing in publicly funded community health centers?

- Develop local agriculture and artisanship to reduce dependence on imports?

- Invest in more public housing or provide vouchers for those with lower incomes so they can afford a decent place to live near where they work?

- Raise the country’s basic living conditions by providing a job guarantee at a decent wage plus benefits to any who want to work?

Every nation has different needs and priorities. It is not our place to promote one policy over another – only to urge a new approach that puts people first and utilizes this powerful tool for public purpose to its fullest.

Is all money created by the government? What about banks?

Is all money created by the government? What about banks?

National GOVERNMENTS CREATE CURRENCY AS THEY “SPEND”. BANKS CREATE BANK DEPOSITS AS THEY “LEND”

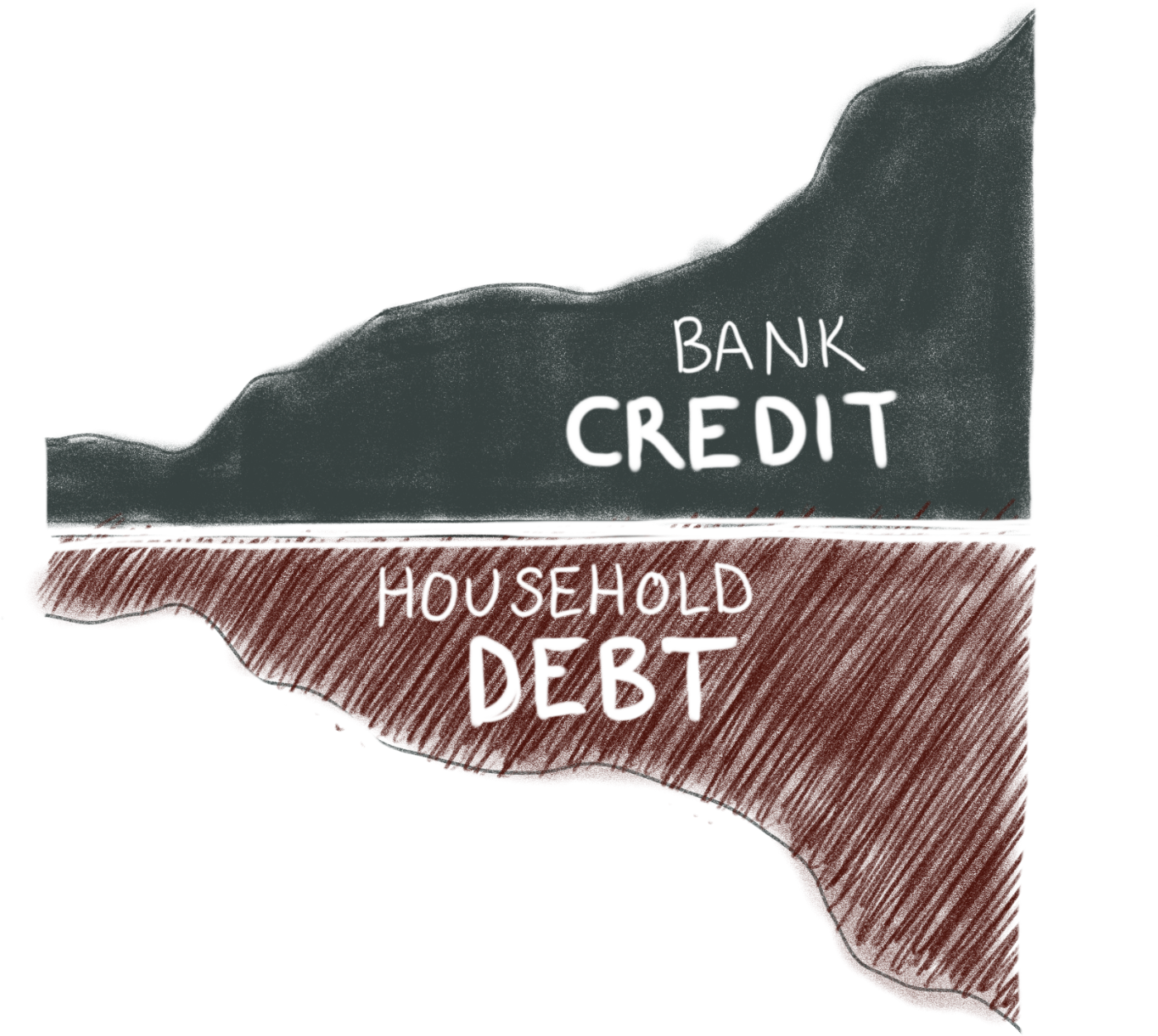

Banks don’t actually “lend” money; they create new bank account deposits by accepting the credit risk of each customer that is willing to repay them over time. Most of the money in our economy is actually created by banks – we will call this bank credit to distinguish it from the government’s currency.

HOW DO BANKS CREATE MONEY?

The government creates new currency as it makes payments by crediting bank accounts, but banks also create new bank deposits each time they extend bank credit to a customer. In modern economies, almost all money is created via the banking system in the form of bank deposits. Banks play a large role in the economy, both in extending bank credit and as an agent for the flows of government currency in and out of the economy.

Each time a business gets a loan for new equipment, or a household signs a mortgage for a house, the bank uses a computer to increase the deposit balance in the customer’s account. In other words, banks accept our I.O.U.s (our promises to repay) and issue their own I.O.U.s (bank deposits). They don’t “lend” other people’s money to “borrowers”.

Similarly, when we use a credit card to buy goods from a store, the store’s bank account is credited with the amount of the purchase. But credit card companies don’t “have” money to “lend”. They simply accept our I.O.U. (our promise to repay the balance each month) and they issue their own I.O.U.s to the store in the form of bank deposits. Each payment creates a new deposit – new money in the economy. Repaying your credit card removes bank deposits from the banking system, redeeming (or extinguishing) the IOU.

We can simplify this by saying that banks “create money” when they expand bank credit and they “delete money” when that bank credit is repaid – which may occur over many years.

Many of us were taught that banks collect money from savers and then lend out that money to borrowers, but this isn’t actually how banking works. Rather, banks have a license from the government to create dollar deposits whenever they accept a creditworthy “borrower.”

WHY ARE BANK I.O.U.’S SO WIDELY ACCEPTED?

Bank deposits have broad acceptance in part because our government insures bank deposits and supports a streamlined inter-bank transaction clearing system. Banks have a special relationship with the government that can be viewed as a kind of public-private franchise of the government’s currency. This perspective provides insight into how and why banking should be regulated to serve the public’s need for credit and a payments system. Some countries even use a public banking system such as Postal Banking to provide these services to every local community.

CREDIT VERSUS CURRENCY

So the government makes payments by creating new bank deposits and banks also create deposits each time they extend credit. All money in our economy comes from either bank credit (someone’s debt), or is facilitated by government payments.

There is a big distinction worth noting at this stage.

- For every new dollar of bank credit the private sector debt burden grew – perhaps your house mortgage or your company’s new equipment financing.

- However, when the government spends its currency into the economy, no household or business became further indebted. Instead, the recipient received an increased bank balance free of any offsetting obligation to repay.

- This is a vital distinction to grasp: when the government pays for some public service or infrastructure, the private sector doesn’t have to go higher into debt to pay for it. And remember that the government doesn’t have to tax more every time it initiates new investments, but rather only if the economy requires some tax adjustment to manage inflation or other public concerns.

The banking system is integral to how our modern monetary system works and there is much to say about how it can be improved to better serve the public. That topic is beyond the scope of this current project, but you can look up the works of MMT economists such as Bill Mitchell, Stephanie Kelton, Warren Mosler, Randall Wray, and Eric Tymoigne on the topic if you are interested.

Are central banks part of the government?

Are central banks part of the government?

CENTRAL BANKS ARE GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS THAT ARE OFTEN GRANTED SOME LIMITED AUTONOMY SUCH AS MANAGING INTEREST RATES

Governments that issue a national currency typically do so via the combination of a Treasury and a Central Bank, although some countries combine them into one government institution with different departments responsible for each function. These institutions coordinate with each other to credit bank accounts when making payments on behalf of the government and debiting bank accounts when collecting taxes.

Treasury departments and the Central Bank must always coordinate their activities daily to make sure all government payments are cleared, all government bonds are sold at issuance or repaid at maturity, and the target interest rate is maintained.

Given how they are subject to Congressional oversight and legislative power Central Banks are not as independent as most suppose. Nearly all central banks around the world are owned and ultimately controlled by their governments.

WHILE IMPORTANT, THE ROLE OF CENTRAL BANKS IN THE ECONOMY HAS BEEN EXAGGERATED

There is a common perception that the health of the economy is in the hands of the Central Bank. Also, given the common lack of transparency into their operations, they are often viewed with much suspicion. A better understanding of modern monetary systems can help the public bring about a more transparent, accountable, and useful role for our national banks.

Firstly, while they have important roles to play, central banks are not the all-powerful agents that many assume. Fiscal policy – the way the government invests and taxes – plays a much more important role in maintaining a healthy economy than the activities of the Central Bank. During recessions, the amount of money the government removes from the economy in taxes is automatically reduced, and the amount it adds via payments for unemployment and other welfare programs automatically rises without any Congressional action needed. Such a rise in what we call government deficits during recessions is both normal and helpful, and is more powerful in promoting an economic recovery than anything the Central Bank can do.

Fiscal policy could be made even more effective by policies such as a job guarantee to directly address the problem of involuntary unemployment. Central Banks can only try to influence the economy by adjusting interest rates, hoping the changes transfer through business and household behavior to cause more job creation. The effectiveness of this approach is at best slow, if not inadequate.

HOW CAN CENTRAL BANKS BEST SERVE THE PUBLIC?

The essential responsibilities of the Central Bank are usually as follows:

- Maintaining an effective payments system between banks.

- Providing oversight of banks and stepping in to keep the financial system from being affected by banks that get into trouble.

- Managing one or more target interest rates that it believes will affect levels of bank credit in the economy.

- Conducting research and publishing data on the economy.

Understanding modern money provides a fresh perspective with which to reform our financial system, including the role of the Central Bank.

A few key ideas include:

- Establishing a permanent zero interest rate policy. Fiscal policy should be the primary tool for maintaining full employment and a stable economy. Interest rate adjustments are an ineffective and unnecessary policy tool.

- Cease the issuance of Treasury bonds. There is no public purpose served by maintaining the pretense of the government borrowing its own currency.

- Insure all deposits without limit. There is no reason to leave depositors exposed to bank failures, and this also replaces the need for Treasury bonds as safe financial assets.

- Implement a Postal Banking (or similar) institution. This will ensure that all citizens, especially the disadvantaged, have access to community banking, affordable bank credit and other important services.

- Narrow the role of chartered private banks to a basic set of services which include maintaining deposit accounts, facilitating payments and underwriting good credit. More speculative or risky financial innovations should be provided by private institutions without the backing of the Central Bank or Treasury.

- Maintain strict oversight of the quality of bank assets (i.e. make sure they are making good loans). The financial system should be carefully watched for signs of excessive risk taking and bad underwriting practices or fraud that can lead to another financial crisis.

Much has been written on these subjects by MMT economists and scholars and we encourage citizens to become informed and advocate for reforms.

All this said, while it is easy to find fault with our financial system, it is also important to understand what the real problems are and focus on the right solutions. Our monetary system is very powerful and it can be made to serve the public even better with the right changes.

What is money?

What is money?

Defining the word “money” can be a bit tricky in English because we use the same word in more than one way. This is why we have often avoided the word money and instead talk about how the government makes payments or banks issue bank credit. However, since this question arises so often, here are a few important ideas to grasp.

- Money has its origins in a societal context, not from barter.

- Money is first a unit of account – the unit to measure debts or tax liabilities like a meter measures distance.

- Each unit of account has its origins from a societal authority — in modern times this is the state.

- The state also issues money “things” denominated in its unit of account such as paper notes or recorded Central Bank account balances.

- Banks are granted a license to create deposits denominated in the state’s unit of account, and other institutions and entities also adopt the state’s unit for financial purposes, creating a sort of “hierarchy of money”.

How Did Money Arise?

As far back as historians have been able to study, in civilizations all around the globe, money appears to have originated from some form of local authority – a tribe, a temple culture, a city-state, a nation. The earliest money units were often grain weights such as a mina or shekel, and later pound, and were a form of record keeping by authorities. Historians now believe that we invented writing to keep track of debts in communities.

For thousands of years, there appear records of societal obligations: a tax, a fine, a tithe, a tribute, a debt. Historians and numismatists find no evidence that money arose in a barter, coin, commodity or market-exchange context, despite the repeated use of this story in Economics 101 textbooks!

Rather, historians provide us with a far more interesting account of the role of money as a social and legal institution, tied to the formation of civilizations, the maintenance of order among communities, the provisioning of resources for governance, community security and development, and the recording and clearing of debts around seasonal harvests. We may never know the very first use of money but we can learn a lot from what we do know.

The State Unit Of Account Is The Foundation of Modern Money

It is important to understand that the norm is for the constituted government to choose a monetary unit of account for the nation (e.g. Yen, Pound, Lira, Dollar), to issue a currency denominated in that unit which it uses to make payments, and to impose taxes or other obligations as a mechanism for redeeming such government-issued IOUs.

One nation: one currency is the rule. The currency exists first as a mechanism to provision the common needs of the nation. Upon this foundation, there can be a “money hierarchy” of additional institutional and personal IOUs denominated in the state’s unit of account with varying degrees of acceptability (from bank credit to a local bar tab).

We use the term currency in this guide to refer to all the “money things” that the government issues and accepts as payment of the taxes and other liabilities it imposes. Today, almost all currency is in the form of recorded Central Bank account balances, with corresponding credit to the bank balance of a person or entity, although most governments still issue some notes and coins.

We find that money is best thought of as a social and legal institution that societies create to serve the needs of their communities. While this includes commerce and private enterprise, we must remember that we created our monetary system to serve the people: the people are not servants of the monetary system or the markets we design around it.